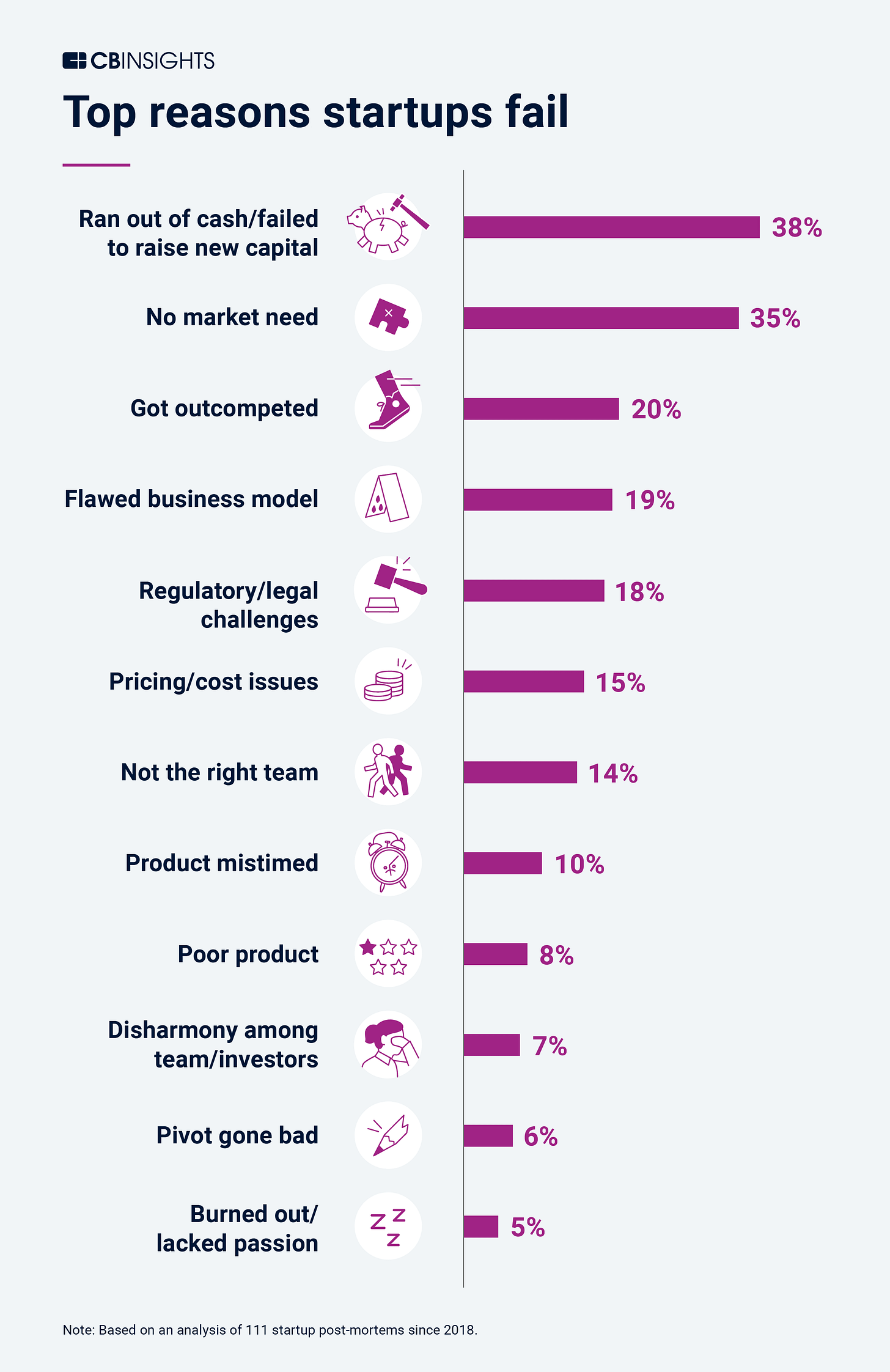

If you have been in the tech scene for a while, you probably have seen this list of startup failures by CB Insights. It’s a very popular list. I’ve seen it on slide one at the kick-off of many accelerator programs to warn founders about the ‘No market need’-trap.

The popularity doesn’t reflect its rigour, though. It’s not based on academic research meeting scientific criteria, and to be frank, it shows. The majority of the categories by CB Insights are self-reported by founders. Perhaps, therefore, the categories on this list are quite ambiguous.

How is ‘no market need’ different from ‘poor product’? How is ‘Ran out of cash’ on top? Is startup failure not, by definition, running out of money? That’s a tautology. It’s like answering the question ‘Why did the ship sink?’ with ‘Because it didn’t float anymore’.

The problem: timing

Among all these vague failure reasons, one stood out to me: the mistiming of the product. I’ve heard founders talk about ‘timing’ on podcasts when listing the reason they failed.

And I always feel a little uneasy. What do you mean, timing? In this article, I’ll do a deep dive in the mythical failure reason: Timing.

It’s everywhere

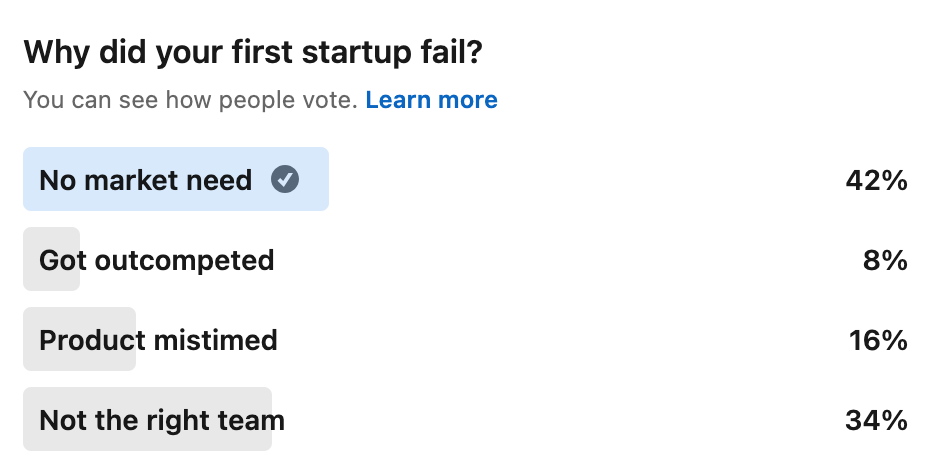

I see timing everywhere. On podcasts, blogs, it’s a dominant explanation. A brief survey among my followers on LinkedIn showed that 16% of founders attributed their first startup failure to timing:

Clearly, the idea of timing is prevalent among our community. But what does it mean?

How does CB Insights define timing?

So what is timing? Well, first, with timing, people don’t mean seasonal timing, like trying to sell snowboards in May. CB Insights defines timing in this report:

#10 – Release product at the wrong time

If you release your product too early, users may write it off as not good enough and getting them back may be difficult if their first impression of you was negative. And if you release your product too late, you may have missed your window of opportunity in the market. As a Calxeda employee said, “In [Calxeda’s] case, we moved faster than our customers could move. We moved with tech that wasn’t really ready for them – ie, with 32-bit when they wanted 64-bit. We moved when the operating-system environment was still being fleshed out - [Ubuntu Linux maker] Canonical is all right, but where is Red Hat? We were too early.”

Here, you can already see the sloppy definitions: “users may write it off as not good enough”. Does that mean the product was not good enough? Because that’s another distinct failure reason: “Poor product”

But the second part perhaps is clearer: “We were too early”. That echoes other quotes from founders CB Insights collected:

A drone company

”History has taught us how hard it can be to call the timing of a market transition. We have seen this play out first hand in the commercial drone marketplace. We were the pioneers in this market and one of the first to see the power drones could have in the commercial sector. Unfortunately, the market took longer to mature than we expected.”

A cancer diagnostic company

”Getting the technology right, but the market-timing wrong, is still wrong, confirming cliche about the challenge of innovating… We may have been right that [a specific cancer aspect] is “hot” and will be important in the future, but we certainly didn’t have enough capital around the table to fund the story until the market caught up.”

It’s psychological: externalisation

To me, this seems to be the founders’ claim that they knew it all and had the right idea and right product ready. It’s just that they were too visionary to get traction: the world wasn’t ready for them.

To them, timing seems a strategic issue, nothing else. If only they had launched their product about 5 to 10 years later, they would have been successful. This is where I smell bullshit. I hope I’m not strawmanning here, but I think timing is an umbrella excuse.

Timing can be a way to externalise your failure, away from yourself, so your ego doesn’t take a hit. To paint an extreme caricature, ‘we didn’t make any mistakes, it’s that the market wasn’t ready’.

However, it could be that sometimes timing indeed is the answer. To combat my pessimism, I will explore whether timing is indeed a valid explanation for innovation failure.

The investigation

To refute my cynical theory, I just need to find one case where it is clear that, indeed, timing is the best explanation for startup failure. If I succeed in my falsification (Popperian) inquiry, I can drop my grudge.

However, to investigate this, I can’t use recent examples of CB Insights. If you say the market wasn’t ready in 2024, likely it isn’t ready in 2026.

Therefore, I’m going through my mental rolodex of innovations that struggled with adoption, much longer ago, with one case stemming from the early 1900s. Because then, we have the power of hindsight to reflect: what did go down, really?

Through these cases, I’ll build a definition of what ‘timing’ means to me, and in the end, after digging through, I found one example that might fit the category. You be the judge. Let’s go.

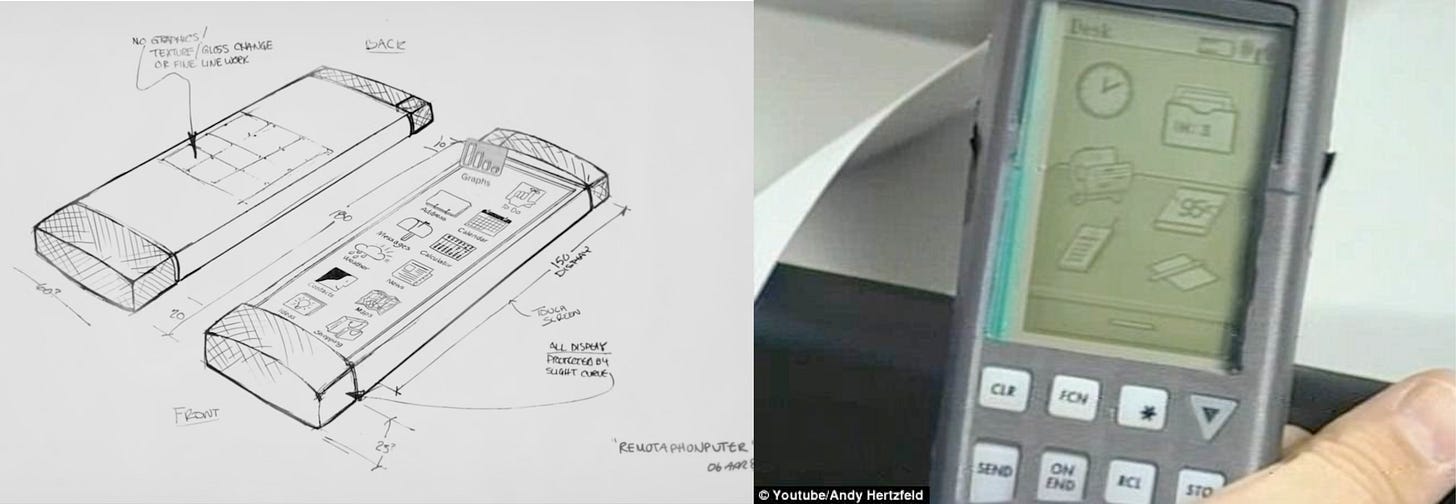

First suspect: General Magic

The 1990 ‘smartphone’ that flopped

The first product that comes to mind is General Magic, the startup that made (one of the) first smartphones. The team had serious talent.

To name a few: Pierre Omidyar, who later founded Ebay. Tony Fadell worked on the iPod and iPhone and later founded Nest. Andy Rubin, who later founded and created Android. Kevin Lynch, who later became CTO of Adobe.

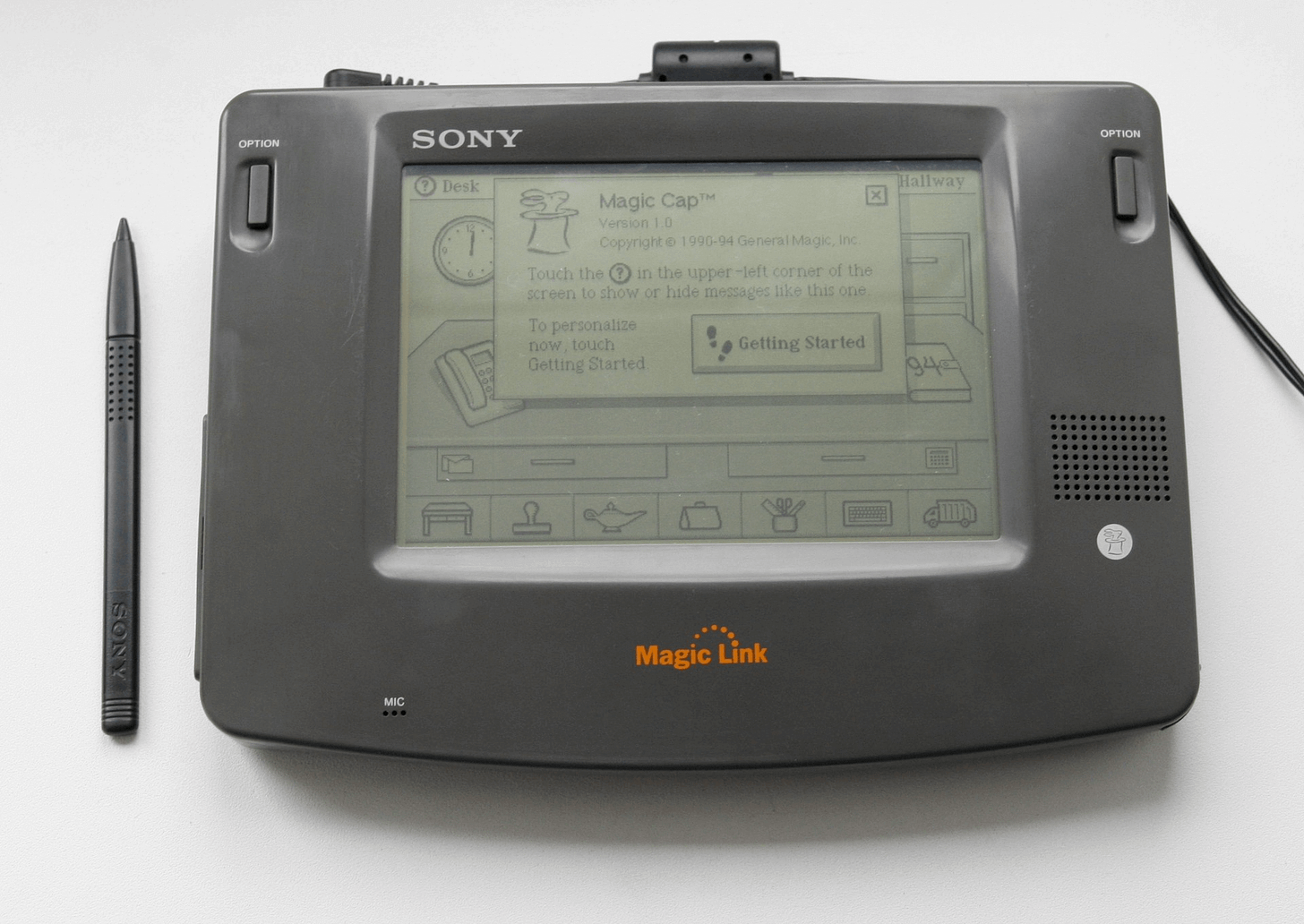

In 1994, the team launched an equivalent of the modern smartphone. They made the software and had initial deals with Sony and Motorola. The device had apps, internet, could make phone calls, and even had emojis. But chances are you never heard about it. Why? Because it flopped, hard.

Why did it fail? For numerous reasons, I’ll list a few.

It was quite slow

The battery was bad.

For the internet on your Sony Magic Link device, you needed to plug in a cable. Yes, very mobile.

The Motorola variant had a wireless modem with a data rate of 4800 bps (0.6 Kb per second); an MP3 song would take approximately 2 hours to download. The MP3 codec was released in 1994, so I guess not many MP3s were downloaded on the Motorola.

The ‘internet’ you could use was not ‘the internet’, but some AT&T private network, as Blackberry did with their Ping messaging.

Initial versions didn’t ship with a web browser.

The screen sucked in most lighting conditions (no backlight), touchscreen was not very responsive.

Furthermore, it was much more expensive than smartphones today: the retail price $800 in 1994 is equivalent to almost $2000 today. In 2026, only a fully maxed-out iPhone Pro Max with 2TB hits that spot, in a very mature market. Breaking the bank for a device that doesn’t work well? Not so surprisingly, it flopped.

Did General Magic fail because of timing?

Tony Fadell, one of the founding members, wrote a book on startups and talks about his experience. In his book ‘Build’ he mentions the timing was wrong. He often states that timing needs to be right. Also, he reflects that having a vision is different from shipping a product. But do they relate to ‘timing’?

Indeed, they had a vision that vaguely resembles a modern smartphone, but you can also see that they have chosen a lot of technologies that weren’t mature enough yet.

Is picking immature technologies a timing issue? You could also argue it’s a design failure. The designers and engineers imagined a device that the technology of that era simply couldn’t support.

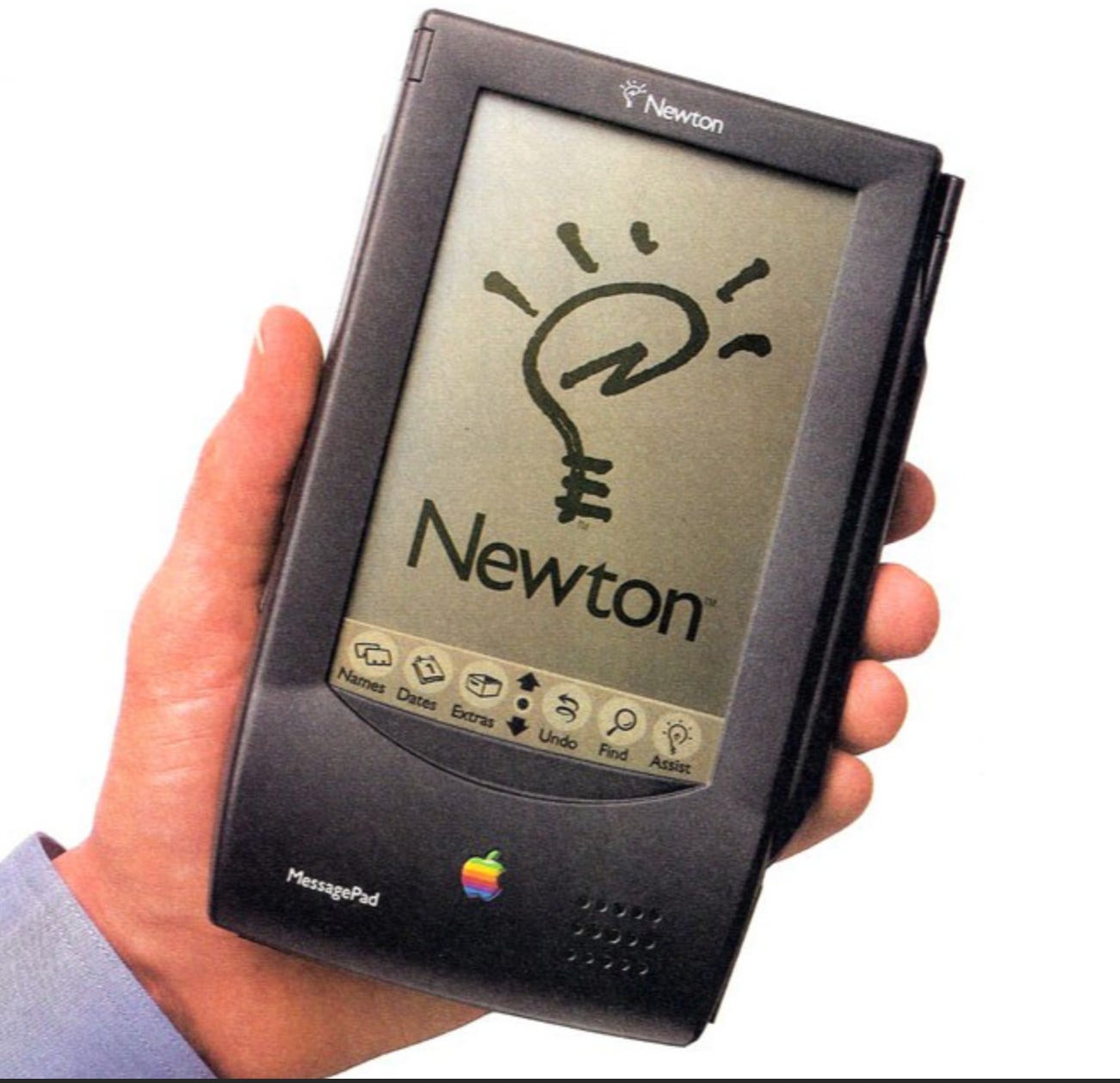

Let’s take the touch screen. That technology sucked back then. Apple’s Newton (early iPad) flopped partially because the touchscreen notoriously sucked so badly that it was impossible to use.

Relying on that immature technology was a mistake. That’s perhaps one reason why Blackberry, for a brief time, took off as a smartphone: buttons were a more reliable user interface. And that is just one of General Magic’s many technological shortcomings.

Actual failure reason: betting on immature technologies

So when people say timing was the issue, sometimes it’s masking another failure reason: building on immature technologies. Which is a more nuanced take. I argue, if this is the case, don’t label it timing, because it doesn’t represent the situation well.

However, there’s an anachronistic aspect to it. We can only say this in hindsight for some technologies. Let’s unpack another example to see what I mean by this.

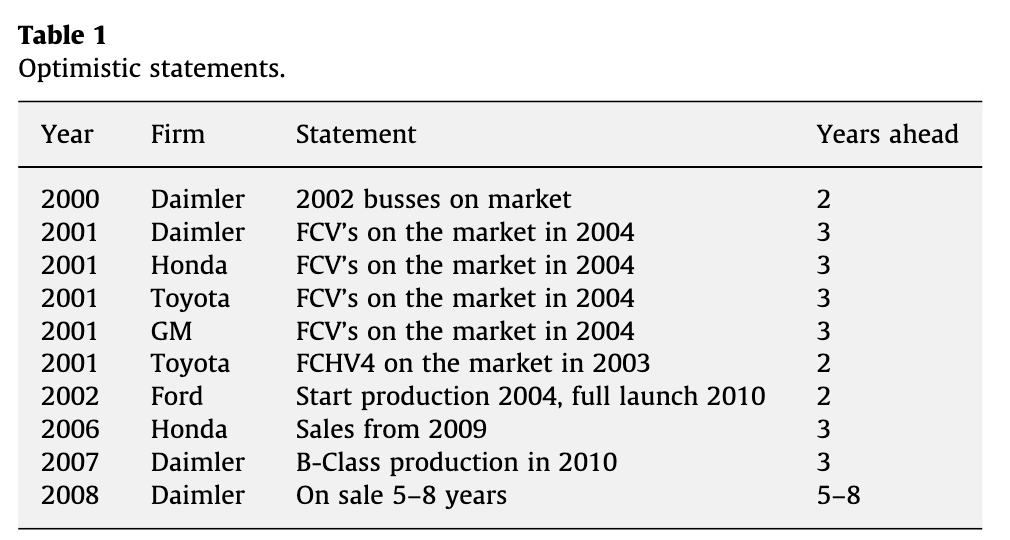

Second Suspect: Hydrogen Cars

It has been promised for years and years.

Around the year 2000, hydrogen as a fuel (for mobility) experienced hype. As more people realised there’s a limited resource of fossil fuels, hydrogen became the saviour.

Hydrogen packs 3 times the energy of petrol, and over 100 times the energy of an EV car battery. Sounds promising, doesn’t it?

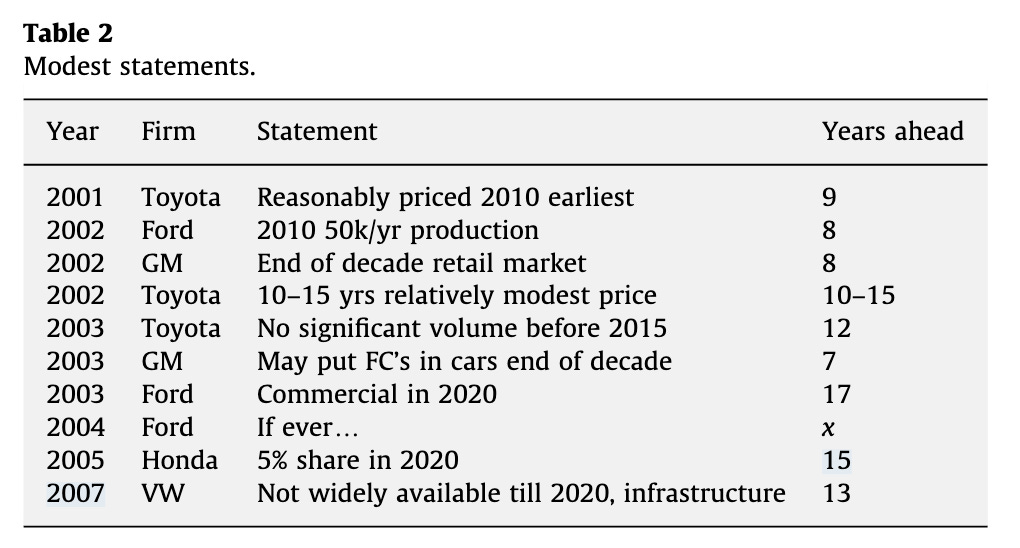

One car manufacturer announced a project to make a hydrogen fuel cell car for the masses, ready in a couple of years. What happened next was a bubble. Car manufacturer after car manufacturer made a similar promise, as visualised below.

In 2003, amidst a post 9/11 Iraq invasion, cynically, the Bush administration invested over a billion dollars with the famous slogan, “the first car driven by a child born today could be powered by hydrogen.” Perhaps this investment was at the political peak of inflated expectations of the technology.

Between all the optimistic statements, researchers found increasingly pessimistic claims emerging (image below). You can see, for instance, how Ford went from ‘Full launch in 2010’ in 2002, to ‘Commercial in 2020’ one year later, followed by ‘If ever’ in 2004. That’s how bubbles implode.

Why did they adjust their prognoses? Simple: The technology was not ready yet. Common critiques: Expensive, lack of infrastructure, and storage issues.

Fast forward to today, despite the potential of the fuel, it’s still not ready in 2025. Hydrogen projects are being cancelled across industries. Airbus cancelled its hydrogen plane as the aviation industry doesn’t believe in it. EVs have made a bigger dent in petrol car sales than hydrogen.

Did hydrogen fail because of timing?

Were all those hydrogen projects ‘timed’ wrongly? Well, that is not the most accurate way of explaining what is going on. You can find ideas and prototypes for hydrogen cars dating back to 1806; that’s two centuries ago. That means that it has taken over two centuries, and we still haven’t figured it out.

Such a trajectory sounds more like a technological challenge, rather than a (strategic) timing issue. You can’t say ‘timing’ is the issue, because the technology hasn’t arrived today. That’s like saying people trying to build teleport or time travel machines failed due to timing.

Actual failure reason: hitting a technological ceiling

Hydrogen failed because it hit a technological ceiling. It’s just not feasible today, or extremely unviable. Sure there are some pilot projects, but you don’t see the mass adoption that was once anticipated.

Still, timing is sometimes used as an argument for the deep tech startups that hit these technology ceilings. For example, this innovative material, graphene, was expected to revolutionise storage and batteries. Despite the Nobel prize awarded for the discovery involving the manufacturing of graphene, it hasn’t lived up to expectations.

So far, it seems that timing is just a lazy way of explaining the lack of technological success. But what happens if we set the technology aside?

Third Suspect: Google Glass

When AR didn’t take off.

Let’s assume people figure out the technology. It mostly works. Then surely, we can find a product that is too visionary for people. There’s this saying that goes ‘Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable’ (MAYA).

Remember Google Glass, which was launched in 2012 and killed in 2015. Was Google Glass too early?

This is me in 2013, a designer friend who interned at Google—I remember being quite jealous—took it to the design school I was doing my Master’s. I remember putting it on, posting a Facebook picture, and you can see the comment that got more likes than my original picture.

The product hasn’t left a rich impression on me, but I remember it kinda worked. But, others have listed it—it was a prototype after all—as buggy, slow, overheating issues, clunky voice and gesture UI, and bad battery life. However, Google Glass had an interesting aspect that is not technological.

Today, bodycams and wearables with cameras are more common, like RayBan’s Meta Glasses. Back then, society didn’t like the idea of being recorded all the time. Even the term ‘glasshole’ was coined for people who wore it anyway. This illustrates the social aspect of innovation.

Was Google Glass mistimed?

Beyond the tech failure, this is an example where there is some societal backlash to new products. Did that stop adoption? Not really. Innovators often ignore the social backlash. For instance, mobile phones were not deemed necessary by the masses at the start.

This video—be sure to turn on English subs—shows the responses of people in 1998, explaining why they don’t need a smartphone: ‘I’m not that important’, or ‘Sounds annoying, being called when cycling’. Indeed, a very Dutch video.

In books, social acceptance is listed as a factor in innovation adoption. But that’s also because you can always find naysayers for any new technology. Was it really blocking? I doubt it was in this case. The product just sucked with a two-hour battery life.

Remember this Rabbit AI pin? It faced a similar backlash. But it didn’t kill the product. The fact that it barely worked, and was just expensive hardware running Android with a simple voice-based LLM that didn’t work well, killed it.

Actual failure reason: no killer feature

Similarly, Google Glass lacked some core killer features that make it highly desirable. Meta-glasses indeed are a thing now, but I barely see them in the wild (adoption seems niche), and I assume it’s mostly being used by TikTokkers to record easily in public, which is a killer feature for them. Google Glass just didn’t create enough value.

So far, the ‘timing’ failure seems to come down to two things:

The technology didn’t work or barely worked, and didn’t provide enough value

The technology was way too expensive for the little value it provided

Okay, it still is quite technological. But what if we find a technology that was ready, and only a social aspect was blocking. For that, you need to hop on my time machine to 1900—A machine I built for the sake of this article.

Sanity check on your product-market fit or go-to-market strategy? Get me as your mentor.

Fourth Suspect: Elevator Buttons

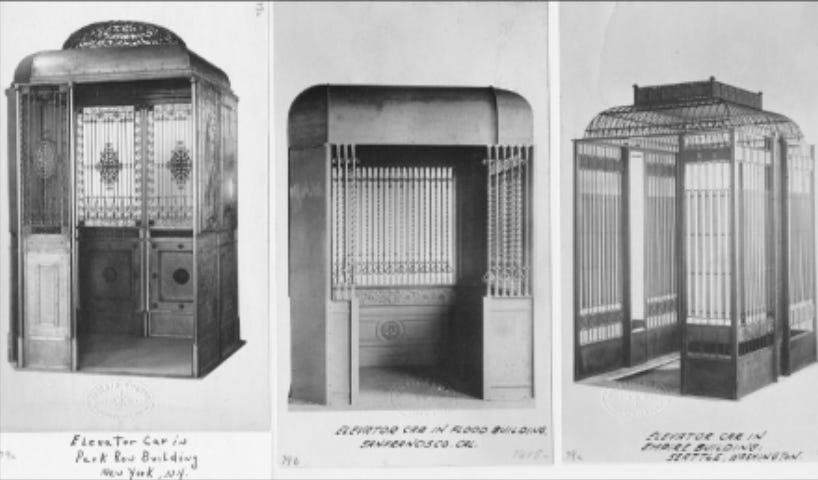

A technology we take for granted, perhaps don’t really see as an innovation anymore are elevators. The vertical people movers originated in the 19th century. Back then, controlling a lift carriage was a skill, almost like operating a tram.

The liftboys needed to stop the elevator manually by operating a lever. The best liftboys could smoothly stop the lift carriage perfectly aligned with the floor it was heading to. Liftboys would sometimes, if the riders were rude or didn’t expect a tip, on purpose leave a gap to annoy the passenger. In my research, I even found a story of a German liftboy who was so elegant in his skill that he even successfully seduced a woman with it—he worked in a hotel anyway, so the next step was closeby.

The liftboy was quite technically apt and could do simple repairs without the need of a mechanic to come. It was quite a different profession as we see it today in most luxury hotels. Why did they disappear? In the first decade of the previous century, elevator buttons were invented.

The competitor of the liftboy: buttons

Elevator buttons enter the market in early 1900s. Indeed some of the new elevators are equipped with the buttons. But, not all. Actually, even though it’s economic, the elevator buttons didn’t take off as expected. That took half a century, only in 1950. What happened?

When the elevator was introduced, people were scared they would drop. Even though the mechanism that would stop a sudden plummet to death worked, the general public really wanted someone professional in the cabin. It made them feel safe. Even the few elevators with buttons still had a liftboy.

It was not only for safety: the liftboy was a host. He would do some unforced small talk, like somebody working behind a bar. That surely fixes the awkward floor staring we often do today. So why did liftboys stay for so long? It was a little bit like ‘this is how we do it’.

Why did it shift?

Most historians point to a strike of 15.000 liftboys (and other lift-related workers) in New York on a day in 1945. Estimated economic damages: $100M. That triggered a lot of building owners to equip elevators with buttons now and get rid of the liftboys: they prefer reliability over luxury.

That was the start of the demise of the liftboy. In the next decades, the carriage operators would make place for push buttons that the peasants control. We now only see liftboys in luxurious hotels or countries where wages are low enough to pay for it.

It’s important to note that in 1950, the Otis Elevator Company launched ‘Autotronic’, which allowed the coordination of multiple elevators of the same building efficiently. This contributed to the adoption. It’s never one thing, but the social backlash has never been so clear for an innovation, requiring a strike to push people over.

Actual failure reason: cultural resistance

I would argue that the dominant ‘failure’ reason for early push buttons for a long time was cultural resistance. The technology worked, but they were just too early to market. So by those lines, we might say, they mistimed their product. But that brings me to another issue I want to unpack last.

Timing hints at strategic deliberation

When you say, “We mistimed our product”, you are also saying you have considered postponing it. Based on my experience working with over 350 startups, I’ve never heard that line of reasoning.

“Maybe we should stop our startup and try it in five to ten years”.

Founders don’t say this, or at least not very often. Sometimes founders ‘shelve’ their product to pick it up later, but that’s just a way to deal with a breakup. I’ve never really seen founders pick it up again after five years.

It’s a verb, too

You might hear people say how they underestimated how long a market took to mature, or for supporting infrastructure to arise, or for technologies to develop, sure. But those are hindsight explanations that don’t have much to do with strategic intentions.

When you say timing, it’s a verb, like segmenting your market. And there you could say: we missegmented our market and therefore failed. But I’ve never seen a founder who wants to postpone the attempt to introduce his product.

Next, most founders don’t have an array of products to choose from. Startups mostly work on trying to get this one thing to work. Timing is not really a strategic consideration.

Debunking the timing myth

Based on my deep dive, I would argue that timing is often an inaccurate explanation of startup failure. It’s an umbrella term that shields the founder’s ego, but doesn’t really show what happened in reality.

Often, there are more accurate explanations for startup failure, like building on immature tech, hitting technological ceilings, getting social backlash, or meeting cultural resistance.

Calling it timing suggests that there is something temporal you can control as a founder, whereas most founders just focus on getting that one idea to market. If you encounter ‘timing’ as a failure reason, from now on, you should ask questions and dig deeper if you really want to learn something.

Verdict: The failure reason ‘mistiming products’ is a myth.

Stop telling yourself you are failing because of timing.

YOU MADE IT TILL HERE. Tell me:

Did you like this deep dive? Let me know by liking the post or dropping your thoughts in the comments. If you have something to nuance or disagree with, that’s even more fun 🔥